How artists have used the frame in the past, & how they can use it now

For centuries artists have understood the power that the right frame can have in presenting and enhancing their work. This is a short article aimed at contemporary artists and art students, in the hope that it may reintroduce them to this power – which has to a great extent been forgotten during the last sixty years or so. It was originally given as a presentation at The Florence Academy of Art in May 2016. A greatly expanded version was given at the Prado, Madrid, in November 2016, and can be seen on video in English and also in a Spanish translation.

Wall paintings from the Tomb of Sirenput I, c.1980-1920 BC, Qubbet al-Hawa, Aswan

The very earliest art that we know of – cave paintings – had no borders, frames or lines of demarcation at all. However, it is clear that as soon as paintings in the modern sense begin to be made, they are almost always associated with some sort of border. These borders are there to contain the image, to divide one scene from another, and to help to focus the spectator’s attention on them. For example, Egyptian tomb paintings from as long as four thousand years ago include scenes which are clearly limited by decorative boundaries: these hold the painted scene, along with the hieroglyphics which explain it – just like a single panel in a modern comic book.

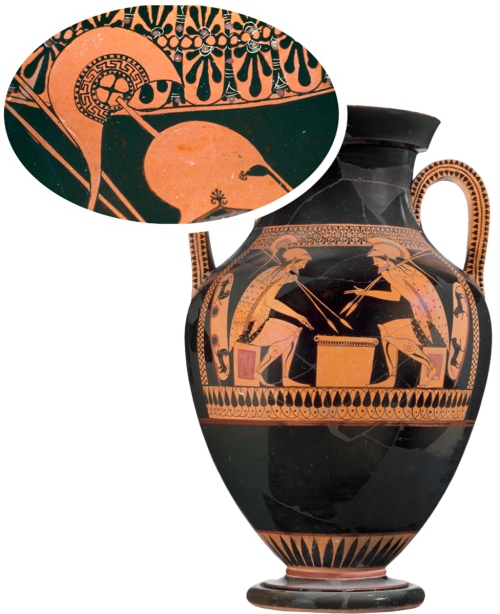

The Andokides Painter, amphora with Achilles & Ajax, c.525-520 BC. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In the same way, figural scenes on Greek vases use increasingly complex bands of geometric patterns or stylized naturalistic ornaments, which help to create and emphasize the interior space of the painted scene, and to separate it from the real world. In this example, the artist is sophisticated enough to play with his frame, breaking through it with the helmets of the two warriors in a sly optical joke.

Sculpted relief with procession of Babylonian warriors, 486-66 BC, Persepolis, Iran. Photo: courtesy of Marina Somers

However, frames also began to develop other functions from a very early period. For example, they could be used to expand upon the meaning of the image they surrounded; in other words, they could be used as an extra field, to carry symbols which related to the painting or sculpture they contained, and to comment on it, just as footnotes carry extra information without interrupting the main text. The sculpted reliefs in the palaces of Persepolis in Iran have borders which, although made of stone, look recognizably like 21st century frames. Many of them – as in the example above – are decorated with carved eglantine flowers, which symbolize protection and long life for the procession of visiting Babylonian warriors represented in the relief.

Altar of Encamp, from Sant Romà de Vila, Andorra, 13th century. Museu d’Art Catalunya, Barcelona

In the modern world – which starts with the end of the Roman empire, and so is not particularly modern – these various functions come together to create the wooden frames which are the ancestors of our own. Public art at this point was almost exclusively religious, and religious images tend to get a lot of use; they are moved about and are often delicate and quite large. Because of this, the frame acquires another function – it becomes three-dimensional, surrounding the image and protecting it. The earliest form of this sort of frame is the raised border around a box-like altar, decorated with painted scenes; the borders are decorated themselves with depictions of precious stones and flowers. These can symbolize (for instance, with the daisy-like flowers in the border of the Altar of Encamp) the humility of Christ, or (in the disc-shaped motifs) the sun-like power of God.

Thornham Parva Retable (36 ¾ x 150 in., St Mary’s Church,Thornham Parva, Suffolk) & Musée de Cluny frontal (37 x 119 in.; 94 x 302 cm., Musée de Cluny Paris), suggesting their original relationship as frontal and dossal arranged on an altar

Later on, the painted image on the face of the altar (the frontal) gives birth to another on top of the altar (the dossal). At this point the frames are as important for the physical support they provide, as for their ornamental and symbolic potential.

Duccio di Buoninsegna (c.1255/60-c.1318/19), The Rucellai Madonna, 1285, 177 x 114 ins (450 x 290 cm), Galleria degli Uffizi

Over time, the panel on top of the altar gradually begins to extend upwards and to take on the silhouette of a church, at first in the form of a simple Romanesque chapel. The reason for this is to suggest to the worshipper that the scene it contains is a vision of the Celestial Church (reinforced by the gilding and jewel-like colours). Duccio’s Rucellai Madonna is the perfect example of what can be done with a relatively simple frame of this sort. Here you have a gabled altarpiece with a chunky but not overwhelming architectural moulding, intended to keep the planks of the retable from warping and protect them from outside damage [i]; and this moulding has a wide flat frieze, providing an extra field around the painting which can be used by the artist. In this case, Duccio (or his workshop) has decorated it with panels of polychrome interlacing on a ground of ultramarine, which echo the Virgin’s robe and reflect the richness of the cloth behind her.

Duccio, The Rucellai Madonna, detail of roundels

The panels are interrupted with roundels containing depictions of saints, apostles and prophets, many of whom turn to look at the Christ Child, an illusionistic device which helps to focus the worshipper’s attention on the main subject. The roundels also serve to open out the meaning of the painting; so that Christ appears in the roundel at the top centre, with figures from the Old Testament on His left, and from the New Testament on His right. The gilded ground of the frame would help, in a dim and candle-lit church, to illuminate these small portraits.

Lorenzo di Niccolò (fl. 1391-1412), The coronation of the Virgin, 1402, San Domenico, Cortona

To complete this very abbreviated early history of frames: the development of the church silhouette from the 13th to the 15th century produced ever more elaborate Gothic analogues of cathedrals, with painted panels occupying the space of the nave, the side aisles, the clerestory above and the crypt below, whilst the sides of the frames grew into three-dimensional tower-like buttresses, to support the weight of the altarpiece. The wooden structure was ornamented with gables and finials, columns, pilasters, and tracery; and any free surface might be painted with inscriptions, geometric decoration, or the symbols and attributes of saints.

But one of the interesting aspects of these altarpiece frames is that they were usually produced by master carvers for the commissioning client before the artist was brought in to paint the subject . Lorenzo di Niccolò’s Coronation of the Virgin, although now in Cortona, was executed for the monks of San Marco, Florence. Their agent commissioned the wooden frame and panels from a carver, Marco de Cori, and when finished it was delivered to the workshop of Lorenzo, who was then given two years to paint it. This was the accepted method of proceeding, and it established the fact that the carver (who might often be a well-known architect, interior designer or furniture-maker) was as important in the production of an altarpiece as the painter.

Botticelli (c.1445-1510), Annunciation, 1489, Galleria degli Uffizi

With the advent of Brunelleschian architecture in the Renaissance, the 15th century altarpiece frame gradually changed from the cross-section of a Gothic cathedral to that of a classical temple. At the same time, the multiple arched painted panels became a single rectangle: the quadro, which showed a scene in which all the figures interacted in a real space – the sacra conversazione. These scenes were much less static than before; they contained figures in action, like a piece of theatre, and the frame became the proscenium arch around the stage. Because these frames are so closely related to contemporary architecture, the effect was also like that of a door or window frame: the spectator could now imagine that he or she was looking through an opening in the church wall onto a realistic scene taking place in another room, or in the landscape outside. In this particular altarpiece, the perspective of the marble floor has been carefully designed to recede from the pilasters and threshold created by the frame, enhancing this door-like effect, and vividly illuminating the partnership between the framemaker and the artist.

Simone Martini (c.1284-1344), St Luke, 1330s, 26 9/16 x 19 ins (67.5 x 48.3 cm). J. Paul Getty Museum

Along with these large Gothic and classical structures, smaller devotional panels had been regularly produced for domestic use, and it is in these that we begin to see wooden frames which are recognizably like those of today. Simone Martini’s 14th century painting of St Luke, with its gold ground and Gothic elegance, is actually a panel from a five-piece hinged altarpiece, and has an engaged frame – that is, a frame which is physically attached to the panel and not removable. Apart from this, Martini’s frame is visually close to the frame of Romney’s 18th century portrait of Mary Casson (below): both are rectangular and of carved wood, with raised rounded mouldings; both are gilded; and they both have small-scale decoration, giving richness to what is otherwise a severely linear design.

George Romney (1734-1802), Margaret Casson, 1781, 35.5 x 27 ins (90 x 69cm), Sotheby’s, 5 June 2008

However, these frames, which are more than four hundred years apart, would have been conceived in completely different ways. As with the large Gothic altarpiece by Lorenzo di Niccolò and the Renaissance altarpiece by Botticelli, the purchaser of the St Luke would have commissioned his five framed panels from a carver. They would probably have been not only constructed but also prepared and gessoed by the carver, who might then have delivered them to an independent gilder; however, the gilding might equally well have been executed by the artist, who would then paint the frieze of the frame or employ one of his apprentices to do so. All these men would have worked as equals in the production of the finished work, and would have been considered by the client as craftsmen of the same status. The carver would have designed the frame; and if carved ornament had been required, he would have designed that as well, probably with reference only to the commissioning client and none at all to the painter.

By the time we get to Romney, however, the arrangement of things is very different. The artist has become the over-riding genius of the operation – sometimes even on a social level with some, at least, of his clients. The client would generally leave the acquisition of the frame up to Romney, who would buy it from his usual carver and gilder. We know that this was Thomas Allwood, up until 1781, and William Saunders from 1781 until Romney’s death in 1802 . Romney would get the frame at a trade price, but would charge the client the full retail price; so he profited a little from using the same carver. He would also choose the style of frame he wanted (here, NeoClassical), the profile, and the ornament – almost certainly in consultation with William Saunders. The client usually accepted what he was given – but then Romney knew the sort of interior his painting would hang in – frequently a house by Robert Adam – and he knew exactly the effect he wanted to achieve from a frame.

Romney, Margaret Casson, detail of frame

This design has what is known as a knulled top edge – in other words, the most prominent moulding of the frame, which is also the outer contour here, has a series of rounded convex shapes clasped across the rail. They are perpendicular to the frame, meaning that they appear to point inward to the painting, helping to focus the spectator’s eye on the subject, and also to enhance the spatial depth within the composition. As well as this, the projecting top edge of the frame means that light is thrown from the gilding onto the image, just as the gold ground of the Simone Martini would help to illumine it by candlelight.

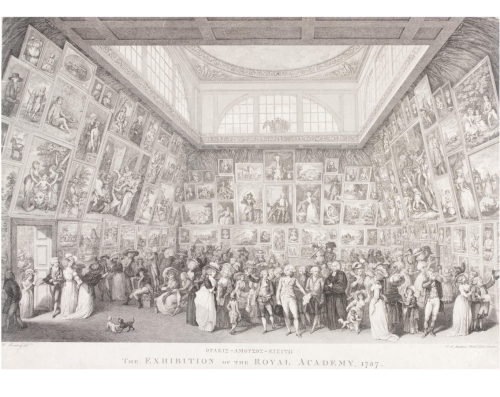

Pietro Martini (1738-97), engraving of painting by J.H. Ramberg (1763-1840), The exhibition of the Royal Academy,1787, 1787, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In the 1780s and 90s, while he was using William Saunders as a framemaker, Romney used this pattern to such an extent that it is now known as a ‘Romney’ frame; so he had also created a trademark design, which would help to identify his work at a distance, and make it stand out on the crowded walls of the Royal Academy, or in a large private collection. This frame therefore works harder for the artist than you might imagine.

The 17th and 18th centuries were a high point in the design of frames in all European countries. Frames were hand-carved, many by master craftsmen; and the majority were water-gilded, giving a purity of tone and what was thought of as a neutral ground around the painting – like the setting of a jewel. Because the carvers and gilders worked in close communication with artists, architects, cabinetmakers and other designers, the frames they produced fitted into contemporary interiors, and artists produced paintings knowing how they would be presented. This meant that they could make use of a fashionable style of frame to enhance their compositions. Baroque frames tend to have large and assertive corner ornaments; and it is noticeable that a great many Baroque paintings conform to the invisible focal lines suggested by this sort of design, and very rarely have skewed or asymmetric compositions which would undercut the geometric forms suggested by these lines.

Diego Velasquez (1599-1660), Don Pedro de Barbarana, c.1631-33, 78 x 437/8 in. (198.1 x 111.4 cm), Kimbell Art Museum

For example, Velazquez’s Don Pedro de Barbarana is defined by the lines between the leafy cartouches carved onto his frame. His upper body sits in the triangle between the centre cartouches of the top and side rails; the hand on his sword-hilt is highlighted by a smaller triangle; and the centre vertical neatly bisects him. The picture gains stability from these coinciding lines, and the spectator’s gaze is naturally guided to the important focal points of Don Pedro’s eye and his sword-hand.

Jean-Etienne Liotard (1702-89), Julie de Thellusson-Ployard, 1760, pastel on vellum, 70 x 58 cm. Museum Oskar Reinhart, Winterthur, inv. 278. Rodolphe Dunki, Geneva; acquired 1935

In the case of Liotard’s pastel of Madame de Thelusson, the diagonals between the corners contain her face, and the centre horizontal cuts her hand, drawing attention to the intimate gesture she makes towards her husband’s pendant portrait, and also drawing the eye down her arm to his miniature portrait on her bracelet. This frame is a stunning example of Rococo carving, with asymmetric swirling motifs and scrolling lines which echo the curvaceous folds of hair and costume in the painting. It was probably made by a French Huguenot carver; a group of craftsmen who spread the highest quality of carving through Europe.

Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), George IV: coronation portrait, 1820-30, Chatsworth

The Napoleonic wars and the industrial revolution destroyed much of the market in hand-carved frames in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. No-one could afford costly items at a time of war; and the coming of early methods of mass-production, along with a growing middle-class who wanted affordable luxuries, meant that the carving and gilding arts were reduced (in Britain) by the early 19th century to a 60th of their previous size. This also meant that the centuries-long relationship of artists and their framemakers became a much more superficial arrangement. Frames were now produced entirely in pinewood, which was not as costly as harder or less common woods; decorated instead of carving with moulded composition ornament (compo); and (in the cheapest versions) gilded with base metal leaf.

Lawrence, George IV: coronation portrait, detail, showing loss of ornament in top left corner

The consequence was that ornament tended to become much smaller, less sculptural, and to proliferate over the surface of the frame. As well as appearing, in the more extreme cases, fussy, and lacking the organic softness of carved wood, compo contained linseed oil, which dried out very slowly over time, eventually becoming brittle and prone to chip away.

Frederick Mackenzie (1787-1854), The National Gallery when at Mr J.J. Angerstein’s house, Pall Mall, watercolour, 1824-34. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

At the same time, frame design became much more limited in its sources, more or less confining itself to antique or reproduction 17th and 18th century styles (mainly French and Italian), which were very unsuitable for many paintings. So long as something was gilded and ornate, it was seen as appropriate to set off both Old and Modern Masters. The result of this can be seen in a watercolour of the National Gallery, London, in its first home in the 1820s. Many of the pictures are set in antique Louis XIV or Louis XV frames, put on by previous collectors – even Sebastiano del Piombo’s large painting, The raising of Lazarus, on the right, dating from 1517-19, is in a Baroque French frame – and those others without antique frames have been given reproduction versions, decorated in compo. Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne (1520-23) on the right of the door, and Aelbert Cuyp’s Hilly river landscape (c.1655-60) above it, are both presented in similar frames, which have no relationship to their nationality, period, composition, style or meaning, and which would almost certainly have horrified their authors.

By the mid-19th century artists had begun to rebel against these commercialized and inappropriate forms of framing. In Continental Europe there were the Nazarenes, like Victor Orsel, and Gothic-Romantics like Auguste Couder; whilst in Britain the pioneers were the Pre-Raphaelites, led by Ford Madox Brown and Rossetti.

Ford Madox Brown (1821-93), Jesus washing Peter’s feet, 1852-56, reframed 1865-66, 116.8 x 133.3 cm, Tate

The frame designs of the latter were radically innovatory, compared with stock Salon frames. Instead of scrolling lines and curlicues, they used geometric forms – straight lines and squares, triangular sections and canted sloping planes – opposed to circles, semi-circles, and reeds with half-round sections.

Ford Madox Brown, Jesus washing Peter’s feet, detail

They followed the teaching of John Ruskin, who believed that no material should pretend to be something it wasn’t – so composition which pretended to be wood was undesirable, and so was gilding on a layer of smooth gesso, since this was pretending to be solid gold or ormolu. Therefore Pre-Raphaelite ornament was carved from wood whenever possible, and gold leaf was often applied directly to grainy oak wood, giving texture and interest to areas of gilding.

D.G. Rossetti (1828-82), Astarte Syriaca, 1876-77, 72 x 42 ins., Manchester City Galleries

Where gessoed surfaces appeared, they were combined with what, in Victorian England, was a spareness and minimalism strikingly at odds with the general horror vacui of much applied decoration. Rossetti’s large, later paintings pair a wide canted frieze between simple mouldings, with carved medallions like sliced fruit, hinting at seduction, fertility, or possibly the apples of Sodom. They provide a powerfully emphatic focusing device, and the roundels function much like the corners and centres of a Baroque frame, helping to reinforce the compositional lines.

Camille-Léopold Cabaillot-Lassalle (1839-88), Le Salon de 1874, 1874, 32 x 39.4 ins (81.5 x 100 cm). Christie’s, 21 January 2009

Although these geometric designs do not appear very extraordinary now, the effect upon audiences at the major exhibitions must have been electric. Here, above, is a painting of how the French Salon looked in 1874, with the paintings crushed together in almost identical moulded gilt frames, like bricks in a wall of golden mortar. Below is a photograph showing the drawing room of one of Rossetti’s major patrons, as it would have looked from 1881, with the paintings in their minimally decorated borders spaced out along the brocaded walls.

F.R.Leyland’s drawing room, 49 Prince’s Gate, 1892, photograph by Harry Bedford Lemere, courtesy of The English Heritage Archive, no. BL1152849

A colour montage gives a better impression of how one of the groupings in Leyland’s hanging would have appeared (the centrepiece, The Blessed Damozel, has a frame which is partly a joke, and partly too a strongly individualistic assertion of the artist’s aesthetic right over his work).

Decorative and symbolic frames were also important in 19th century Russia, developing independently from the 1840s and 1850s. In this case the client or patron was an important catalyst for custom-made patterns, but many artists were soon involved in designing their own settings.

Vasiliy Pukirev (1832-90), The Unequal Marriage, 1862, carved giltwood frame by craftsman Grebensky (fl.1860-70s). State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Vasiliy Pukirev’s painting, The unequal marriage, is autobiographical, showing the artist’s mistress forced into a marriage of convenience with a much older man. The artist stands behind the bride on the extreme right, and the carver who made the frame is shown between the heads of the bride and groom. He was a friend of Pukirev, and decided to produce a frame which would comment on the subject with as much satiric force as the painting; so he made a design which has a conventional frame structure, and overlaid it with a carving of withered branches entwined with fresh and blooming flowers. This gives an added edge to the work, especially for the symbol-obsessed 19th century viewer.

Vasiliy Vereshchagin, The Apotheosis of War, 1871, artist’s frame with moulded ornaments. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Vasiliy Vereshchagin designed individual frames for most of his paintings; this one is perhaps more subtle than Pukirev’s. It merely sets a garland of bay leaves – the traditional reward for victory – around a composition which shows the inevitable defeat for all sides in war. The very coarse sand which has been used to give texture under the gilding echoes the sand of the desert, and provides an unusually strong ornamental band. The colour of the gold leaf used is also important here; the deep reddish orange tinge reflects the desert sand and heightens the innocent blue of the sky.

In the second half of the 19th century, travel became so easy that artists commuted rapidly between countries, visiting foreign exhibitions and sharing and diffusing ideas. Individually-designed artists’ frames were soon appearing throughout Europe and America, along with functions which had died out with the Renaissance, such as inscriptions. These became as popular as symbolic motifs, and can be seen on paintings of many nationalities.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Danseuse au repos, 1879, pastel & gouache on paper, in a white frame designed by the artist. Sold at Sotheby’s New York, 2008 in a different frame

The Impressionists used frames differently from the Victorians; Degas, for instance, copied the reeded and fluted geometric mouldings used by the Pre-Raphaelites, but employed them as minimalist borders in neutral white, or as an avant-garde columnlike bundle of reeds, which functioned as perspectival device to reinforce his novel, japonist use of space. The Impressionists also introduced the idea of off-setting a picture with one over-riding tint by a frame painted in a complementary colour. Sadly, scarcely any of the latter have survived; whilst Degas used green (from at least 1873), brown and white frames, Mary Cassatt is recorded in 1879 as using red and well as green, and in 1880 Pissarro exhibited frames in complementary colours to the dominant colour of the painting:

‘…pour un soleil couchant à la dominante rouge, un cadre vert, pour une toile violacée, un cadre de ton jaune mat; un printemps d’aspect vert s’enchâsse dans du rose: la lumiére resplendit, plus congrue et plus harmonique.’ For a sunset with a dominant red hue, a green frame, for a purplish canvas, a frame in a matte yellow, and a spring green landscape surrounded by a rose-pink border: the light is enhanced, more balanced and harmonious.[ii]

Pere Borrell del Caso (1835-1910), Escaping criticism, 1874, in trompe l’oeil painted frame. Collection of the Banco de España, Madrid

The rediscovery of the frame as part of the whole work of art, able to interpret the picture, emphasize the composition, or provide a decorative transition to the outer world, also brought the realization that there were no rules as to how these borders could be used. Artists began to play with the idea of the frame, letting the painting break free of it in various ways (and rediscovering what the Greek red-figure vase painter in the early part of this essay had already known). The ‘frame’ above is part of the painting, but designed so that it can fit seamlessly into an actual picture frame (although, of course, it would have to be hung to the right of a window). It allows the artist to imagine that the boundary between the painted and the physical world might actually be pierced, and the personification of grubby realism might escape the strictures of 19th century critics.

Salvador Dalì, Couple with their heads filled with clouds, 1936, 92.5 x 69.5 cm (man), 82.5 x 62.6 cm (woman). Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam

The frame could even be used to create the contours of the picture itself. In Salvador Dalí’s work, the painted background is continuous behind the silhouettes of the lovers, so that the frame actually draws the composition onto the landscape; at the same time, it revisits the idea of the Renaissance frame as a window onto another world.

René Magritte (1898-1967), L’évidence éternelle, 1930. The Menil Collection, Houston

In the set of five canvases by Magritte, the artist paints the body of his beloved as he remembers it in her absence; it is fragmented, as memories are, and the various parts are not in proportion with each other. The frames are undistinguished, but play an active part in creating this idea of a portrait painted at one remove.

This revival of imaginative frames lasted for about a hundred years, and lapsed again after the second world war. But now there are once more practising artists who are beginning to see the possibilities in this no-man’s-land between the real and the painted world; artists who are developing modern versions of custom-made frames – part sculpture, part symbol, part satire.

Mark Ryden, Queen Bee, 2013

For example, the American ‘outsider’ Gothic artist, Mark Ryden, draws what are often very intricate designs for his frames, many of them playing with conventional patterns, and has them executed in Thailand by experienced carvers. He also uses second-hand frames, finding one which was made for a looking-glass and using it for a painting (Meat dancer), and then having it copied for the frame above, with bees and beehives replacing some of the traditional elements. Using salvaged frames is a very respectable and well-established method for artists; Delacroix and Renoir both wrote about frames which they had acquired and which they were producing paintings to fill. Even now it is possible to buy antique frames, especially from the 19th century, including nice hardwood Victorian frames in rosewood or bird’s-eye maple, which are still relatively inexpensive.

Holly Lane, Indwelling, 2014, acrylic & carved wood, 22 ½ x 29 x 8 3/8 ins

Holly Lane (also an American) has gone one step further than Mark Ryden with his Thai carvers, making her own frames from scratch. They are part altarpiece, part furniture, part fantasy architecture. She discovered the potential of frames when she was a student, and saw that they could be used to comment on the painting, or to suggest ideas related to the subject. She taught herself woodwork from books and experiment, and now makes frames which may take longer to create than the paintings. She says of her own work,

‘I realized that a frame could be many things; it could embody ancillary ideas, it could be an environment, it could be a shelter, it could be an informing context, it could be in dialogue with the painting, it could extend movement, it could be like a body that expresses the mind, and many other rich permutations…’

Italian School (possibly Bolognese), A mathematician, c.1600-50, NG22 94, in previous frame. National Gallery, London

Finally, here is an instance of the difference the right frame can make to a picture. It involves the reframing of a work in the National Gallery, London: the artist is unknown, but the portrait is striking. It has been housed for the last hundred years or more in a most unsuitable setting (above) – a French Louis XIII-XIV giltwood frame, with undulating strapwork and sprigs of flowers densely carved in low relief over the major convex moulding. This was too fussy for the spareness of the portrait, slightly too late in period, and completely wrong in terms of national appropriateness. The gilding also tends to flatten the space in the painting, as it presents too great a contrast with the overall tonality of the work. Unfortunately, the head is very close to the top of the canvas, which may have been cut down at some point, and this exaggerates the claustrophobic effect of the old frame.

Italian School (possibly Bolognese), A mathematician, c.1600-50, NG2294, in current frame. National Gallery, London

This portrait has recently been transferred into an Italian reverse frame of the right period (‘reverse’ simply meaning that the highest forward moulding is next to the painting, rather than on the outer edge). The black and gold finish is much more aesthetically appropriate, and the top moulding, with its large fluted gold ornament, opens out the composition and helps to increase the effect of recession into the sitter’s space. The portrait now appears much more lively and dynamic, with a greater feeling of depth. As well as the individual effect on the painting itself, it also fits in much better with those around it, helping the 17th century Italian room where it hangs to have a more coherent and satisfying look, and giving some appearance of context to the spectators.

It’s an interesting illustration of before and after, and it sums up in two neat images the amazing effect a frame can have on a painting. If you are an artist or an art student, please do think about this, and try the effects that different forms of framing can have on your own work.

*************************************************

[i] Unfortunately this structural precaution did not work, since the rigidity of the heavy frame meant in fact that it was unable to flex with the planks of the painted panel, causing the latter to crack apart.

[ii] Lecomte, Camille Pissarro, in Les Hommes d’aujourdhui, no 336, 1890