The Despenser Retable: the iconography of a 14th century frame

Despenser Retable, c.1380-90, Norwich Cathedral.

Despenser Retable, c.1380-90, Norwich Cathedral.

Britain comes off badly in the study of mediaeval and Renaissance altarpieces, compared with Italy and Spain and their riches – or with the Netherlands, Scandinavia and Germany. Even France has retained more of its early retables than the British Isles, where the Reformation and the Civil War saw the destruction of much of our religious art. There are partial survivals such as the 13th century Adisham Reredos, in the church of the Holy Innocents, Adisham, Kent; but if you want to get an idea of what a great High Gothic 15th century altarpiece would have looked like in all its coloured and gilded glory, you must seek out the rood screens in parish churches – there are still some extremely beautiful carved and painted screens surviving, many of them in Suffolk and Norfolk (although even here the faces have been erased, in an effort to preserve the rest of them from the iconoclasts).

Central screen, left side, late 15th century, St Edmund’s, Southwold. Photo: Simon Knott of Simon’s Suffolk Churches

Central screen, right side, late 15th century, St Edmund’s, detail. Photo: Simon Knott of Simon’s Suffolk Churches

Just as later altarpieces were linked in structure, pictorial composition, materials and technique to these screens, so the frames of their earlier forebears were related to the borders of illuminated manuscripts and contemporary wall paintings, and to the stone mouldings framing the monumental reredoses which are the façades of Gothic cathedrals.

Façade of Wells Cathedral, West Front, c.1230-60 & later. Photo: David Iliff. Licence: CC-BY-SA 3.0

Façade of Wells Cathedral, West Front, c.1230-60 & later. Photo: David Iliff. Licence: CC-BY-SA 3.0

The tiers of niches and arcading of diminishing sizes, the buttresses, the sculpted figures, the bands of quatrefoils, canopies and finials, which together decorate – or even form – the façades of cathedrals such as Wells, Salisbury and Exeter, are elements in gigantic versions of altarpieces: just as the altarpieces themselves are designed as a vision of the Celestial Church. The cathedrals would have seemed even more like reredoses when they were first constructed, since the statues they held would most probably have been painted and gilded, as would much of the framework which held them.

The delineating borders and mouldings of these cathedral façades, and of wall paintings and architectural openings such as doors and windows, were outlined in geometrical patterns, stylized flowers and bands of colour. We know, for example, that the Painted Chamber in the Palace of Westminster, London (which was redecorated from 1263 after a fire), contained windows where the frames were gilded with black lines, or painted in red, green or blue. Other more elaborate techniques, which had been employed on altarpieces, were also transferred to an architectural context: panels of glass, gilded and painted on the reverse and applied to wooden surfaces, were used on both the interior and exterior of churches to simulate the colour and gloss of enamelled plaques. This was one of the methods used to decorate the Westminster Retable (c.1270-80), our largest and earliest surviving altarpiece.

The Westminster Retable, c.1270-80, 36 x 132 in. (95.8 x 333.5 cm), Westminster Abbey, London.

Unfortunately, not very much of it has survived intact. Unlike many painted religious panels torn from their frames, which are then destroyed, this is mostly an intricate, beautiful and battered frame from which the paintings have been mercilessly scratched – not during the Reformation or the iconoclasm of the 1640s, but in the 18th century. It is made like a jewelled reliquary, and is influenced by the interiors of the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris[1] – covered with panels of painted glass, faux enamel, pastiglia and cameos. It is linked both to miniature metalwork shrines and reliquaries of Anglo-French work in the same period, and also to the great painted and gilded tombs built like small houses within the mediaeval cathedral. It looks as well towards the Painted Chamber, which held the state bed of Henry III:

‘The paintings around the bed included the expensively-finished image of the coronation of St Edward within the bed enclosure, imitating the glass inlay and fabulous bijouterie of the French-looking [Westminster] retable.’ [2]

Westminster Retable, c.1270-80, detail, left-hand panel with St Peter

Like other mediaeval British retables which survive, it follows contemporary and later German, Spanish, and many Netherlandish altarpieces in retaining a rectangular outer frame, whereas Italian examples have a church-shaped silhouette from at least the last quarter of the 13th century. This linear frame means that such altarpieces remain close to their roots in the façades of painted or metalwork oblong box-shaped altars. Within its defining rectangular contour, the Westminster Retable has five panels of different widths: three with micro-architectural frameworks, which echo the structure of Italian Gothic altarpieces, and two with Saracenic eight-pointed star-shaped inserts. The outer framework, the dividing rails and the frames of these stars were once opulent with gold and brilliant colours, as can be seen from the borders (above), with their faux enamel plaques (painted parchment overlaid with glass) and spaces where gems or glass cabochons were laid.

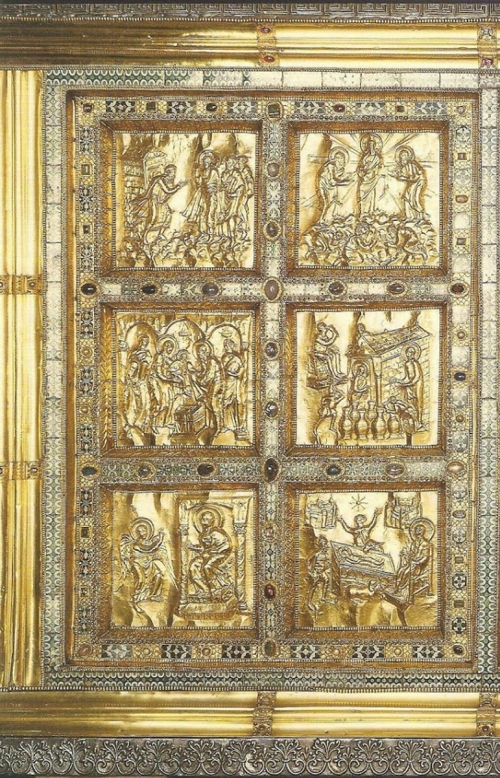

Magister Phaber Vuolvinius, Altare d’oro, 824-59, 120 x 220 cm., detail: left-hand panel of three. Sant’ Ambrogio, Milan

These borders are related to those of much earlier altars, which might be worked in precious metals and mounted with real jewels and enamel plaques: for example, the Altare d’oro, in Sant’ Ambrogio, Milan, which was made in 824-59 from sheet gold and silver-gilt on a wooden carcase, and is still used as an altar and as a saints’ reliquary. The frame of the Westminster Retable is strongly reminiscent of borders on this type of three-dimensional precious altar, although it replaces répoussé gold with gilded gesso; the background within the stars and niches is also diapered all over on gold leaf. It imitates the jewels on works like the Altare d’oro with semi-precious cabochons and antique cameos, whilst the spaces between the star shapes are filled with a honeycomb of cells holding rich ultramarine glass mosaics picked out in gold scrollwork.

Btitish altarpieces in this reliquary style were extremely expensive, in terms both of the materials and the labour involved: in 1258 Peter of Spain received £80 (a huge sum at that time) for executing the frontal and dossal retables for the Lady Chapel in Westminster Abbey (i.e. the framed and painted panels which respectively decorated the front of the altar and stood on top of it) [3]. Henry III also commissioned a frontal made of fabric and embroidered with jewels, cameos and enamel plaques, for the even more extravagant sum of £280. This was to be used on the High Altar when the Abbey was consecrated in 1269, and it is suggested that this was the celebratory frontal, which would cover the more mundane fixed frontal – possibly the Westminster Retable itself [4].

Thornham Parva Retable, c.1330s-40s, 36 ¾ x 150 in., St Mary’s Church, Thornham Parva, Suffolk

The altarpieces of the Abbey, of which the Westminster Retable is indisputably one of the most important, provided models for Gothic altarpieces throughout the kingdom. One of these (and another of the very few remaining to us) is the Thornham Parva Retable of the mid-14th century – this, as perhaps the Westminster Retable also was, is one of a pair of frontals and dossals, the frontal panel of which is in the Musée de Cluny in Paris (37 x 119 in.; 94 x 302 cm).

Reconstruction of relationship of Thornham Parva and Musée de Cluny retables, showing frontal and dossal arranged on an altar

These panels were made in the same workshop, and it is generally accepted that they were executed for one of the altars of Thetford Priory in Norfolk. This Dominican Priory contained a statue of the Virgin which worked miracles, and the frontal of the paired panels shows scenes from the life of the Virgin; whilst the dossal, the Thornham Parva Retable, has eight panels of saints appropriate to a Dominican foundation, in niches surrounding a Crucifixion [5].

Detail of the Thornham Parva Retable, left side, and St Anne teaching the Virgin, from the Musée de Cluny frontal, right side

Like the Westminster Retable, both panels are held in a flat outer frame which slopes into the pictorial surface via a scotia (hollow), or a canted sill, with a small astragal at the sight edge. This combination gives definition and focus to the paintings, helping them to stand out from their surroundings – an emphasis which is reinforced by the painted patterns and complementary colours of these frames. Large areas of gilding are reserved for the backgrounds of the nine niches on the dossal, and for the details of ornamental borders, crowns and haloes, but there was probably also gilded decoration, now lost, enhancing the frames.

Harley MS 616, f.1, c.1313-09, with detail inset. British Library

The composition of the pictorial elements and the finish of the patterned borders follow very similar features in contemporary or slightly earlier illuminated manuscripts: see, for example, the series of six small panels showing God creating the earth in Harley 616, folio 1, where the architectural niches, diapered grounds and flat patterned frames provide an almost identical model for the Thornham Parva and Musée de Cluny retables. There is no attempt in these altarpieces to imitate precious stones or inlays, either with gems, glass or moulded gesso; the frame seems to be moving on from the inheritance of early metalwork altars towards the simple painted flat or canted outer mouldings shared by altarpieces in other northern countries, and to a similar stylized floral or geometric decoration .

Despenser Retable, c.1380-90, Norwich Cathedral

The Despenser Retable displays a further stage in the development of the English altarpiece. It was executed roughly fifty years after the Thornham Parva pair, which in their turn can be dated about fifty years after the Westminster Retable. Although it was made in an East Anglian workshop at some distance from London, it would be a mistake to label the workmanship provincial. In the 13th century Norwich still occupied a very prominent position amongst the hierarchy of English cities, probably second only to London, with a population of around 10,000. It commanded communication with Germany and the Low Countries, and was placed at a major intersection of trade routes, as they flowed across the North Sea to spread out through Britain. Norfolk was as relatively populous as London and the south-east are today, and the county was rich in agriculture, castles and monastic foundations. The wool and leather industries had made Norwich wealthy, too; the great wool churches of East Anglia clustered around this large commercial city – which contained sixty-two churches of her own – and her bishops were powerful men.

Despenser Retable: coat of arms of Henry le Despenser (restored over original trace on gesso layer). Photo: Paul Hurst ARPS

One of these bishops was Henry le Despenser (c.1341-1406), the patron who commissioned the altarpiece; a member of a clutch of Norman-French siblings who fought under various banners in England, France and Italy, and a cleric from his extreme youth, he became bishop of Norwich at the age of 29. Eleven years later he led an army of men against the rebels of the Peasants’ Revolt, who had occupied Norwich, putting down this arm of the rebellion with great brutality. It has been suggested that he commissioned the retable as a thank-offering for his success against the rebels, although it cannot be dated accurately enough to confirm this idea, and it is equally possible that Despenser was offering it against his own salvation, and – or – commending the donors who had contributed to his cathedral and to the retable for its High Altar. This would explain the number of coats of arms which originally figured on the frame along with his own armorial bearings, including those of Sir Stephen Hales, Sir Thomas Morieux, and the Howard family.

Despenser Retable before restoration (reconstruction); it had been reduced from the size indicated by the fawn areas

The retable was hidden away from the destruction of the Reformation, but unfortunately it was at some point turned upside-down and converted to a work bench; it was rediscovered in 1847 in a room above one of the chapels in Norwich Cathedral. It had lost the upper eighth of the picture surface, the top rail of the frame, four further stretches of the lateral rails (when legs were fitted at the four corners), and three of the vertical dividing mouldings, where the bare oak wood of the horizontal boards was exposed [6]. It had also lost most of a series of (hypothetically) twenty-eight faux enamel panels placed along the frieze of the frame, of which those remaining (three) or having left a visible trace (another three) indicated that a good proportion – perhaps all – depicted armorial bearings.

Despenser Retable: section of frame, using b-&-w line diagram by Pauline Plummer in cited article [7] (the panel with dice is a modern replacement. Photo: Paul Hurst ARPS)

As well as these indications of an iconographical aspect to the frame, there was also enough of it remaining for its physical complexity to be obvious. It has moved some way from the flat border and inner hollow of the two earlier altarpieces; this is an English cassetta frame, built up from a variety of mouldings. There is still an outer flat fillet, painted dark green and decorated with gold flowers, but this then contains an ogee painted red, with small gold florets; a gilded astragal; a wide flat frieze; another gilt astragal; a narrow canted frieze painted either blue or red, with gold florets; and a final gilt astragal at the sight edge. The last two astragals enclosing the canted red or blue frieze form an inner frame around each painted panel [8].

Despenser Retable: reverse of panel showing the four original oak boards & one replacement. Photo: Paul Hurst ARPS

Despenser Retable: lateral view of altarpiece, showing junction of two oak boards (right) & the back edge of the frame fastened to the front of the panel (left). Photo: Paul Hurst ARPS

The frame is about 6 ½ in. or 16.7 cm wide, and it was applied on top of the picture panel, after the latter had been put together from the five horizontal boards which originally formed it (the upper board was lost along with the top rail of the frame, as noted above). The frame is level on each side with the edge of the panel, as can be seen here. All the joints were secured with wooden dowels; the whole altarpiece, panel and frame, was then covered all over with a thin layer of gesso [9]. The end of a canvas tape can be seen on the right; this has been applied over the joints, presumably in the 1958 conservation process.

Despenser Retable: detail of gilded gesso ornament on background of Crucifixion scene

Like the Westminster and Thornham Parva retables, the Despenser Retable sets its figures against gilded backgrounds. Although its various scenes, with their creation of shallow perspectival space and dramatic interplay, are more naturalistic than in either of the other altarpieces, they still use a decorative ground of raised gesso ornament covered with gold leaf to set off their painted figures. In the case of the Crucifixion and the Ascension, the ornament is also symbolic, using heart-shaped vine-stems holding Eucharistic vine leaves; the other scenes seem to have more random arrangements of acanthus. The gesso here was applied by hand to the smooth layer covering the whole panel and frame; it was probably mixed to the consistency of a clay slip, or thick cream, and put on with a brush.

Despenser Retable: panel of gilded gesso ornament on frieze of frame. Photo: Paul Hurst ARPS

Similar gilded gesso ornament covers the frieze of the frame in between the panels with coats of arms; here it is decorated with S-scrolls of vine (or more probably berried ivy) leaves. The panels themselves are most clearly described by Pauline Plummer, the conservator who restored the altarpiece in 1958:

‘…panels 8.4 x 6cm., formerly of glass painted on the underside to imitate enamel, which were fitted into slots cut in the inner beading [astragal]. Three of these pieces of glass survive, two in a broken condition and all three having been removed and re-set at some time. They are painted in the form of armorial banners in red, black, and silver leaf, and are mounted on pats of adhesive putty, in some cases red, in others black, which lie over the gesso ground of the frame. Traces of this material remain even where the glass has disappeared, and three more arms can be identified by the imprint left on the putty while still soft. They are all arms of Norfolk families of the 14th century, the three original being the arms of Hales, Morieux, and Howard, while those identified by traces on putty are the coats of Despenser, Kerdeston, and Gernon.’ [10]

Despenser Retable before restoration (a reconstruction): trace of Despenser arms, top left; original arms of Hales and Morieux, bottom rail

Despenser Retable before restoration (a reconstruction): trace of Kerdeston and Gernon arms, left & centre; original arms of Howard, right

Thirteen panels, traces of panels, or sites for lost panels remained on the altarpiece in its unreconstructed state; if the panels had continued around the frame in the same symmetrical pattern, there would be a total of twenty-eight. The question then arises as to what filled those sites where the panels have been lost. Were they all armorial bearings? Is this an altarpiece which acknowledges donors from twenty-eight noble or gentle families in Norfolk? The idea that it was commissioned as a gift to the city of Norwich in gratitude for the help given to Henry le Despenser in quashing the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381 began, according to Sarah Stanbury, with an article by the Victorian historian and archaeologist, W. H. St John Hope [11].

As she points out,

‘Of the identifiable six banners, three can be traced to families that played prominent rôles in the suppression of the 1381 rebellion – namely, Sir Stephen Hales, Sir Thomas Morieux, and most significantly, Henry Despenser, bishop of Norwich from 1307 to 1406… Three banners hardly constitute evidence that the altarpiece was given as a thank-you gift for suppression of the revolt; in her entry on the altarpiece in the Age of Chivalry catalogue, Pamela Tudor-Craig does not even mention this supposition, stating instead that “no doubt the heraldry commemorates not only those who contributed to the altarpiece itself, but those who had helped fund the reconstruction of the eastern arms of the church.” ’

She also adds that,

‘…The banners painted on the frame, coupled with the absence of any mention of the altarpiece in the sacrists’ rolls, strongly suggest that it was a lay gift’ [12].

Giotto di Bondone, The stigmatization of St Francis, 1297-99, from San Francesco, Pisa; now Musée du Louvre; with detail of the stemma of the Cinquini family. Photo: Sailko

If we compare this retable with Italian altarpieces of the same era or earlier, we can see that the frame was already a field to be employed – as well as for inscriptions relating to the painting, purely decorative ornament, and sacred symbols – for coats of arms belonging to the donor or the relevant city. This one (above) by Giotto, painted a century before the Despenser Retable, identifies the work as a gift from the Cinquini family of Pisa to the church of San Francesco through two tiny coats of arms on the frieze of the frame. These are so small in relation to the altarpiece as a whole as to preserve the humility of the donors more or less intact.

Fra Angelico, Madonna & Child with two angels, c.1420, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

A Fra Angelico Madonna, from thirty or forty years after the Retable, demonstrates the more usual wish of the donor to brand their offering as visibly theirs – either so that the Almighty should make no mistake in bestowing credit where it was due, or so that the congregation of the church should be equally well informed. These frames with armorial markings are, however, each definitely the gift of one family, or of various branches or marriage lines within the one family. Collective gifts were nearly always made under the umbrella of a guild or religious company, where the individuals were subsumed under their group insignia. It is unusual, to say the least, to find up to twenty-eight separate armorial bearings on one frame. The idea that the Despenser Retable might therefore represent the gift, not just of the altarpiece itself, but of collective funding for refurbishment or rebuilding of the cathedral, is entirely logical.

Seal of Henry le Despenser, with his coat of arms (right) from Despenser Retable (restored over original trace), and insignia of the See of Norwich (left; modern extrapolation). Colour photos: Paul Hurst ARPS

It should also be noted that, although the Bishop led the suppression of the Peasants’ Revolt, the Despenser arms are not displayed in the centre of the frame, but halfway up, on the left-hand rail. This does not seem to indicate a particular wish to celebrate his part in ending the rebellion; and the knights who helped him do not have their arms displayed more prominently than those of other families who were not involved. Despenser’s relative modesty has been slightly skewed by the 1958 restoration, which has added his mark as a bishop – the three mitres of the See of Norwich – to the right of the central cross on the bottom rail.

Despenser Retable: coat of arms of Norwich Priory (modern extrapolation). Photo: Paul Hurst ARPS

The restoration had one great difficulty to navigate: how to deal with the lost glass panels on the frame. The original size and probable form of the overall structure was recreated, along with the missing board from the panel; and the top of the central painting reinstated in order for the retable to function again as a sacred object. It would have been possible to repaint the upper parts of the frame and the lower corners and to leave them with the ornamental gesso restored, but with blind panels where the original pieces of decorated glass might have been supposed to have been sited; but presumably it was thought that this would detract too much from the symmetry of the frame, and would also distract from the paintings.

Despenser Retable: coat of arms of the See of Canterbury (modern extrapolation). Photo: Paul Hurst ARPS

It would have been impossible to resurrect the arms of other Norfolk families, without misleading the spectator with false evidence which pretended to be historical; so the three extrapolated panels were kept strictly within ecclesiastical bounds. Pauline Plummer describes what was done, without – unfortunately – disclosing how this decision was arrived at:

‘…a set of twenty-five new glass panels was prepared, with the arms of the Priory, Sees of Norwich and Canterbury, and a series of Passion symbols. The glass used was 17th century, of several greenish tints, and showing a variety of weathered surfaces. Before painting, these were further coloured on both sides with a yellow glaze… The designs were painted in egg tempera, and gold and silver leaf applied with gelatine. All were dulled down and damaged to make them resemble the three original glasses as much as possible’ [13].

Despenser Retable: Passion symbols (modern replicas) clockwise round frame from lower left; from left to right here, both rows: Vera Icon; the Grail/Eucharist; lantern and four torches; Peter’s cockerel. Photos: Paul Hurst ARPS

The ‘Passion symbols’ were an appropriate and unexceptional way of filling in the missing panels, and maintaining the spirit of the retable as a sacred object. A useful comparison is the iconography of a Tuscan or Venetian aedicular frame in the collection of the V & A, London ; it is much later than the retable (1475-1500) and sculpturally more sophisticated, but the predella panel, carved with the instruments of Christ’s Passion, reveals how the decoration of a frame could be used to expand, through a programme of symbols, upon the meaning or scope of the painting or sculpture it contained. The five paintings of the Despenser Retable, covering events in Christ’s Passion from His flagellation to the ascension, might in this way be enlarged upon, through other events recalled to the worshipper’s memory by the emblems on the frame. The four symbols (above) are taken from the frame from the lower left, travelling clockwise; they include the veil of St Veronica with which she wiped Christ’s face as he carried the Cross through the streets of Jerusalem, and which retained a perfect impression of His face (the Vera Icon); the Grail or cup used at the Last Supper, and echoed in the Eucharistic cup, here with the circle of the Host, or bread; the lantern and torches with which the Roman soldiery came to arrest Christ; the cockerel which crowed three times after Peter had denied that he knew Christ.

Despenser Retable: Passion symbols (modern replicas) clockwise round frame from top left; from left to right here, both rows: pitcher; pillar and whips; crown of thorns; the pelican in her piety. Photos: Paul Hurst ARPS

The next four symbols come from the top of the frame, reading from the left: the pitcher of gall and vinegar which Christ was given to drink on the Cross; the pillar and whips of the Flagellation; the crown of thorns which was put on Christ’s head; and the pelican feeding her young with her blood, which is a type of Christ.

Despenser Retable: Passion symbols (modern replicas) clockwise round frame, top moving right; from left to right here, both rows: robe of Christ; dice; nails; sponge, sword and lance. Photos: Paul Hurst ARPS

These symbols include Christ’s robe, which was gambled for by soldiers at the foot of the Cross; the dice which they cast for it; the nails with which Christ was fastened to the Cross; the sponge on a stick, with which He was given vinegar to drink, and the sword and lance of Longinus, the second of which pierced His side (Longinus was the apocryphal centurion, who converted to Christianity after the Crucifixion; he is the chap in red with embroidered gold doublet, pointing up at Christ in the central panel of the Despenser Retable).

Despenser Retable: Passion symbols (modern replicas) clockwise round frame, right side; from left to right here, both rows: ladder, pliers and hammer; rebus of the Trinity; wounds of Christ; inscription from the Cross. Photos: Paul Hurst ARPS

The symbols on the right-hand rail include the ladder, hammer and pliers associated with Christ being nailed to and then taken down from the Cross; and a tri-partite rebus representing the Trinity. This consists of three golden discs labelled, clockwise, ‘Pater”, ‘Filius’ and ‘Spiritus Sanctus’, joined on the outside in a continuous band by the words ‘non est’ and to another disc in the centre (‘Deus’) by the word ‘est’. In other words, the Father is not the Son, who is not the Holy Ghost, who is not the Father; and the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Ghost is God. This pleasing visual and verbal pun also echoes pictorially the coat of arms of the See of Canterbury. The last two symbols on the right side of the frame are an emblem of the five wounds of Christ (in His two hands and two feet, and in His heart, pierced physically by Longinus and metaphorically by the sins of the world); and the Latin inscription which was nailed to the top of the Cross: ‘INRI’, and which translates as ‘Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews’.

Despenser Retable: Passion symbol (modern replica), bottom left-hand corner: the Lamb of God. Photo: Paul Hurst ARPS

One final emblem is the Lamb of God, in the bottom left-hand corner of the frame; this is another type of Christ; it is haloed and carries a banner with a red cross.

Altogether, these symbols work very successfully to expand the story of the Passion from the five scenes shown on the painted panel to a much broader conception of its scope. It now extends from the Last Supper, through Christ’s betrayal by Peter and by Judas, and His arrest, by the way of the Cross, the Crucifixion and Deposition, to the Eucharist, the Trinity and two types of Christ. The arrangement might be queried, in that it is natural to read these symbols in a clockwise direction, and they do not follow this direction chronologically; on the other hand it might also be suggested that the general populace of the 14th century, not being natural readers nor accustomed to use clocks, would not necessarily read the symbols in this way. Given that whatever other armorial bearings there may have been could not be replaced, these symbols of the Passion are the most satisfying alternative, and have been replicated in an equally satisfying way. There is also no reason to assume that the coats of arms would necessarily have continued around the whole frame; it is perfectly possibly that some symbols of the Passion were originally included – at least along the top rail.

Despenser Retable: coat of arms of the Howard family (original faux enamel panel). Photo: Paul Hurst ARPS

The Depenser Retable occupies an important and evocative position in the art of the British Isles, standing in for so much that has been lost. It demonstrates – in its emotional depth, its spatial awareness, its elegance, colour and beauty – the sophistication which pictorial art had reached in East Anglia in the late 14th century. The frame, too, is as developed and complex as Italian cassetta frames of the same period, and the type and variety of decoration is strikingly rich and well-organized. The six identifiable coats of arms by themselves indicate, if not a political alliance to put down rebellion, at least an alliance of important Norfolk families in support of their cathedral, their priory and their city. The restoration is also important, since reconstruction of the panel and the frame have given life back to the altarpiece as a functioning object of sacred art, and the intelligent recreation of an emblematic programme for the frieze has renewed the work without reducing it to a mechanical reproduction. In Sarah Stanbury’s words,

‘…Splendid in its use of painted glass to imitate enamelling, the frame effectively wraps the Passion narrative in a neat and orderly package, one that is hieratic, hierarchical, and above all local.’ [14]

Despenser Retable: coat of arms of Sir Thomas Morieux (original faux enamel panel). Photo: Paul Hurst ARPS

**************************

With grateful thanks to the Dean and Chapter of Norwich Cathedral for permission to publish images of the Despenser Retable, and to Paul Hurst ARPS for allowing me to use so many fine and detailed photos of the work.

Despenser Retable: coat of arms of Sir Stephen Hales (original faux enamel panel). Photo: Paul Hurst ARPS

**************************

[1] The interior of the Sainte-Chapelle was damaged and looted during the French Revolution, and was restored during the 19th, and again during the 20th-21st, centuries, so it seems not particularly helpful to show images of it here. The Musée de Cluny houses objects from the Sainte-Chapelle.

[2] Paul Binski, ‘The Painted Chamber at Westminster, the fall of tyrants and the English literary model of governance’, Journal of the Warburg & Courtauld Institutes, vol.74, 2011, p.144.

[3] Aron Andersson, ‘Review: E.W. Tristram, English Mediaeval wall painting: the 13th century’, The Art Bulletin, vol. 34, Sept. 1952, p. 242; this review also suggests that the Westminster Retable is part of this pair of altarpieces by Peter of Spain, rather than the dossal (or frontal) of the High Altar in the Abbey.

[4] Ibid.

[5] From the left, the saints in the Thornham Parva Retable are: St Dominic, St Catherine, John the Baptist, St Paul, St Peter, St Edmund, St Margaret and St Peter Martyr.

[6] Pauline Plummer, ‘Restoration of a retable in Norwich Cathedral’, Studies in conservation, vol.4, no 3, August 1959, p. 108

[7] Ibid., p. 109

[8] Ibid., p. 108

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Sarah Stanbury, The Visual Object of Desire in Late Medieval England, 2007, p. 78; the article she mentions is by W. H. St John Hope: ‘On a painted table or reredos of the fourteenth century, in the cathedral church of Norwich’, Norfolk Archaeology, vol. 13, 1898, pp. 293-314

[12] Ibid., p. 79

[13] Plummer, op. cit., p. 114

[14] Stanbury, op. cit.