Strigillated frames: the ripples of Mannerism

by The Frame Blog

Strigillated ornament on frames is a small but notable fashion in the 16th century, linked to the Mannerist games played with other classical ornaments. It makes an eye- and light- catching setting for a painting, thrusting it forward for the spectator’s attention and isolating it from the decoration on surrounding walls.

Titian (fl.1506-d.1576) or workshop, A boy with a bird, c.1520s (34.9 x 48.9 cm); recently reframed. National Gallery, NG 933

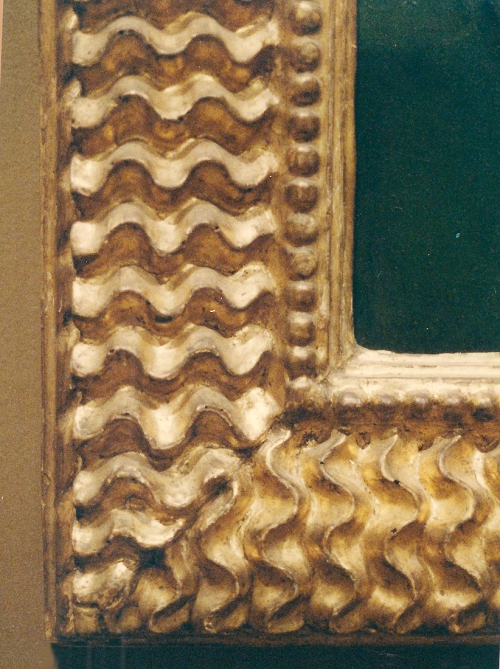

Francesco Salviati (1501-63), Portrait of a man, c.1550-55, J. Paul Getty Museum; detail of frame, showing strigillated ornament. Photo courtesy of Paul Mitchell

The strigil is an archaic combination of soap and massaging implement, used to scrape oil, dead skin and dirt from the body by Greeks and Romans – by athletes especially, but also in the baths, by ordinary citizens. It is curved, and often developed an S-shaped undulation which characterizes the ornament we know as strigillation.

Bronze athlete’s toilet set consisting of an aryballos (oil-flask) and two strigils, linked by chains to a ring for hanging on the wall; c.1st-2nd century AD; BM 1868,0105.46 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Strigils are found in graves as part of the accoutrements needed for the afterlife, or as an offering; they may be decorated and made of silver, rather than the more functional iron or bronze. In spite of this evidence of their social value, their only association with the curving flutes of strigillated ornament seems to be purely visual, and is probably an 18th or 19th century link – satisfactory modern shorthand for a particular motif.

Great Colonnade (Cardo Maxima) at Apamea in Syria, 2nd century AD

Straight flutes are a very common classical architectural decoration, appearing as the parallel concave channels running down Doric and (later) Corinthian columns, and in painted form on Greek vases. It only needed a twist, as it were, to make these into the spiralling flutes which decorate the columns of, for instance, the Great Colonnade or Cardo Maxima in Syria. See also (for example) the Tempietto del Clitunno in Spoleto. In this guise they have absolutely nothing to do with strigils; but the impulse to reuse ornaments, wasting nothing, and continually tweaking them to suit different needs, turned the three-dimensional spiralling flute into a two-dimensional panel of cropped spirals or S-scrolls – Hogarth’s line of beauty – which we now call strigillation.

Roman sarcophagus, no date, no identification, Octagonal Courtyard, Vatican Museums

Repeated in parallel, these S-scrolls or strigils give an optical vibrancy and sense of movement to the surface they decorate; they can also cause the illusion of the flat panel bowing out into an ogee, creating a dynamic tension with other elements of – in the examples below and above – a rectilinear sarcophagus.

Roman sarcophagus with Bacchus, Silenus & a bacchante, no date, Octagonal Courtyard, Vatican Museums

This tension is also used by the sculptors in these examples to focus on the figurative panels, highlighting them, and echoing or contrasting with the lines of the carved bodies to enhance a sense of movement.

Roman bath, Palazzo Barberini, Rome

An impressive use of the optical illusion created by strigillation decorates the surface of a large Roman marble bath in the Palazzo Barberini; in this case the ornament also conjures the idea of rippling water, in a nicely attributive fashion [1].

Roman (Antonine) strigillated marble vase, 2nd half of 2nd century AD, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Strigillation was also used on the curving bodies of vases, where the synchrony of the flowing line with the swell of the vase creates a radiating swirl, like the petals of a flower. A particularly good example of this is an antique snake-handled vase in the Metropolitan Museum, the snakes possibly indicating that this might have been a funerary urn. They writhe and circle on either side of the vase, echoing and emphasizing the spiralling movement of the flutes beneath them, and in this exaggerated torsion – combined with the distorsion of the classical flute – there are evident some of the features which made strigillated ornament so sympathetic to 16th century Mannerism. This flux and torsion is redolent of the inherent Mannerism in Hellenistic sculpture, and, for instance, in the Laocöon group (excavated in 1506). The link with death and interment is also a continuing association in the use of strigillation; as Roman sarcophagi were adopted by early Christians, the motif began to accrue another layer of symbolism.

Sarcophagus of St Eusebia, 4th century AD, re-used in 9th or 10th century AD, Saint-Victor, Marseille. Photo: Xavier de Jauréguiberry

As Elizabeth Fischer’s thesis on the ‘strigil motif’ sets out, strigillated sarcophagi were first used in what we would call ‘classical Greece’, were popular in the Roman empire from the 2nd-6th centuries AD, and were re-used from the end of the 9th century AD until perhaps the 13th [2]. Replica sarcophagi were also produced from the 9th century. Fischer sees this as evidence of the ornament itself being important in this appropriation and recreation, as an abstract motif which lost its abstract qualities when it was re-interpreted from a Christian viewpoint. Such an argument gains strength from the apparently greater frequency of re-use for antique sarcophagi with strigillation [3]. Re-used sarcophagi were very often associated with the bodies of saints, the connection with the antique creating a closer link to the time of Christ, and the miracle-working features of the relics transferring itself to the physical container, so that pilgrims wished to see and if possible touch a particular sarcophagus [4]. Eusebia was an important local saint in Marseille, and the sarcophagus (above) appears to have been chosen for her remains above the many others available, some of which had more complex sculptural façades; the niche in which it now sits was tailor-made for it in the 13th century [5].

Sarcophagus of St Eusebia, detail of left-hand sculptural scene

Fischer notes the dynamic qualities of strigillation, which would appear to move under the change of light and shadow as a pilgrim approached the coffin of a saint [6], implying continuing life in the place of death. She also relates the pattern to water, especially in scenes of Peter or Moses striking a rock and producing water – the subject of the left-hand scene on St Eusebia’s sarcophagus [7], where the water flows in an S-shaped curve next to the strigils. Flowing water such as this signified the giving of both physical and spiritual life (through baptism), and thus was also associated with the passage through death to new life. A watery motif like the repeated wavy strigil was therefore very suitable for sarcophagi, and also for altars and fonts, the other purposes for which antique sarcophagi were re-used [8]. This continued to be the case in later representations; Fischer notes, for example, a miniature of the burial of St Edmund in a strigillated sarcophagus, in a mediaeval MS in the Pierpont Morgan Library, dated c.1130.

Andrea Guardi, tomb of Davanzati with early Christian sarcophagus, 1444-46, Santa Trinitá, Florence. Photo by Baldiri

Strigillation became popular again in the 15th century, with the change from a Gothic to a classical idiom; this time early Christian sarcophagi were also re-used, as is the case with the tomb of Giuliano Davanzati, in Santa Trinitá. The tomb as a whole is probably by Andrea Guardi (fl.1440s-70s), who was as enthusiastic about the antique as Brunelleschi [9]. Guardi may have trained in the workshops either of Bernardo Rossellino, or of Donatello and Michelozzo. The sarcophagus he chose to re-use for the tomb of Davanzati had an advantage over an actual classical example, in that Christian imagery in the form of a panel with the Good Shepherd was already present, set against a heavily strigillated background. This combines at once the idea of Christ caring for his flock, like Davanzati (a public servant in Florence), with the idea of Christ as the sacrificial Lamb destined to rise again, as well as a rippling waterfall of baptismal and nourishing waters.

Strigillated altar frontal, before 1459, Chapel of the Magi, Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence

A decade or so after this, an example of a custom-made altar frontal, rather than a re-used sarcophagus, was installed in the chapel of the Palazzo Medici. It is carved from red Maremma marble, and has been tentatively attributed either to Michelozzo or Bernardo Rossellino [10], with either of whom Andrea Guardi may have worked. It was commissioned by Cosimo de’Medici some time before 1459, and has been identified with the altar described in the 1492 inventory of Lorenzo the Magnificent’s possessions. Given its position, in the private chapel at the political heart of Florence, this is a particularly telling piece of evidence in support of the continuing popularity and use of strigillation as a decorative motif during the 15th century, and reinforces Guardi’s use of the same ornament on Davanzati’s tomb. It demonstrates that this was an ornament which had by this time entered both the decorative and the symbolic vocabulary of contemporary sculptors, opening the way for its diffusion onto other elements of an interior – and secular ones – such as furniture and frames.

Walnut cassone with strigillation Italian, 16th century, Detroit Institute of Arts. Photo courtesy of Paul Mitchell.

The cassone, being related in shape to both sarcophagi and altar frontals, was an obvious candidate in decorative terms to be enriched with strigillation; the bellied shapes of 16th century cassoni also meant that the optical effects of repeated strigils fitted the surface perfectly to the form. It became one of the characteristic ornaments of Mannerist carving, along with exaggerated volutes, flutes and gadrooning. And just as the Mannerist ‘Sansovino’ frame found correspondences in contemporary furniture and fittings, so strigillated frames became fashionable for 16th century paintings and their accoutrements [11].

Palmezzano (1460-1539), Holy Family with John the Baptist, c.1530, Phoenix Art Museum Sadly this image cannot be published, since no-one at the Phoenix AM responds to permission requests

A good example of the genre is the carved cushion frame now on Palmezzano’s Holy Family with John the Baptist. It’s one of the purest and generally most effective uses of strigillation, relying on a single large moulding completely covered with a rippling fall of overlapping wave forms – perhaps more ‘M’ shaped than ‘S’ shaped. The melting leaves at the corners and small subsidiary ornaments at the back and sight edges hardly impinge on this shimmer of slightly irregular undulating scales, which halo the painting in a coruscating sunburst of light. By Elizabeth Fischer’s criteria, it is ideally suited as the setting for this painting, since it brings together the idea of living waters, resurrection and baptism with the figures of the Infant Christ and the Baptist; ironically, however, Palmezzano’s work remained almost entirely untouched by the tides of Mannerism swirling around him, and a tranquil cassetta frame with a gentle pattern of arabesques might have suited him and his Holy Family much better.

Alonso Berruhguete, Salome with the head of John the Baptist, c.1512-16, Galleria degli Uffizi.

Alonso Berruhguete is far more in the expressive Mannerist fold, and his sensual, long-fingered Salome caressing the platter containing an ecstatic head of John the Baptist is much more appropriate for a strigillated frame. This is a late 16th – 17th century cassetta, with the strigil motif cut across the width of the frieze. In spite of its antique derivation, it appears here as an anarchic and non-classical ornament, curling like undisciplined dahlia petals around a subversion of the Madonna and Child; this strange, surreal and erotic painting has found its perfect partner. Echoes of the saint’s calling are summoned in the repetitive waves which seem to flow around his head, symbolizing both the waters of baptism and the blood of his martyrdom, prefiguring the blood of Christ.

Spanish or North Italian School, Head of John the Baptist, c.1550-1650, Cleveland Museum of Art

A similar juxtaposition is found with the frame on a head of John the Baptist in the Cleveland Museum of Art. Again, the symbolism is (probably fortuitously) perfect, and the strigillation provides the same watery flicker around the saint’s head. The painting was formerly classified as circle of Titian and is now labelled Spanish/ North Italian school. Strigillated sarcophagi were exported widely from Rome, and many examples are found in Spain; but strigillation does not seem to have been adopted there as a carved ornament. It would probably have harmonized with the softly-carved and chunky fleshiness of leaves and fruits on Baroque Spanish carnosa-style frames, but strigillated ornament appears to have been restricted in Spain to the spiral fluting on straight and Salomonic columns. The frame of the Cleveland painting is almost certainly mid-16th century Italian.

Bronzino (1503-72), Pierantonio Bandini, c.1550-55, oil on wood, probably poplar, 106.7 x 82.5 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

In spite of the symbolism implicit in these frames, a greater number of them now is probably used to frame Mannerist portraits than sacred subjects. For example, a version very close indeed in its profile and decoration to the example on the Cleveland Head of John the Baptist now frames the magnificent portrait of the connoisseur, collector and banker, Pierantonio Bandini; both frames have the same six orders of ornament, including an interrupted gadrooning of the top edge, and an idiosyncratic imbricated leaf-&-bud motif just above the stylized leaf tip to the sight edge [12]. Possibly they may even be products of the same workshop.

Details of frames: Spanish/North Italian School, Head of John the Baptist (top right); Bronzino, Pierantonio Bandini (bottom left). Photos courtesy of Paul Mitchell

It is not clear whether, in view of the religious symbolism with which this particular ornament seems to be invested, strigillated frames would indeed have been used on secular portraits of the period; the few Mannerist portraits which show framed pictures or looking-glasses as part of the composition seem invariably to favour an ebonized or walnut cassetta. However, there is equally no reason to suppose that a pattern which had accrued symbolic significance could not be used as a purely decorative feature in a secular context, as on cassoni. The composite ornament of the design above is visually extremely effective in the case of the Bronzino portrait, where there is no religious sub-text; it provides an opulent, light-catching border around the pared-down silhouette of the sitter, effectively isolating him from the interior where the portrait would hang, and using the inward-pointing rays of the strigils to focus attention upon him.

Lotto (c.1480-1556/57), Triple portrait of a goldsmith, Kunsthistorische Museum, Vienna. © KHM-Museumsverband

The same is true of Lotto’s triple portrait of a goldsmith, in Vienna. The frame on this painting has been cut down quite radically to suit the very narrow composition, but the same close focus and claustrophobic space of the portrait which has caused this reduction has also found its perfect partnership, in a convex profile with radiating and emphatic ornament. This is very similar to the cushion frame on the Palmezzano – a wide band of strigillation with leaf corners, but bounded here by the same leaf-&-bud top edge as the sight edge on the NG of Canada and Cleveland paintings [13]. The immediacy of the portraits is only increased by light shimmering over the ridges of the strigils on the frame, creating a persuasive sense of movement in the sitter(s).

Francesco Salviati (1501-63), Portrait of a man, c.1544-48, J. Paul Getty Museum. Photo courtesy of Paul Mitchell

Salviati’s portrait has an even simpler frame than the Palmezzano – a wide river of centred double strigils between a small spiral ribbon and beading, it appears a very long way from the classicizing ornament of a Renaissance frame, even though the strigils are close in their plainness to their classical source. The frieze they sit on is very slightly cambered, and they are deeply carved into the wood: three-dimensional flanges, which reflect the gilding from each other and set up a continual vibration of light around the portrait. This must have seemed incredibly avant-garde when it was made: so divorced from the organized proportions of a cassetta frame, so little – apparently – architectural, so ungeometric. At the same time, it looks forward to the milled decoration of the 17th century – the ripple and wave mouldings which, on a much smaller scale, would play with light on a polished ebony frame.

Titian (fl.1506-d.1576) or workshop, A boy with a bird, c.1520s, National Gallery, NG 933, in previous frame

Reframing the National Gallery’s A boy with a bird was an easy argument, with a strigillated frame available in the same pattern as the Palmezzano frame. This small painting was acquired in 1876, as part of the Wynn Ellis Bequest of 44 paintings. It was cleaned several years ago, and a fascinating investigation revealed that it was painted over another image, and that it was almost certainly either the product of Titian’s own hand (‘a slight and hastily executed work’), or by a member of his workshop [14]. It had been put into a ‘Watts’ frame, that ubiquitous and catch-all solution to everything from portraits to history paintings and aesthetic harmonies in the last third of the 19th century. The ‘Watts’ pattern is based on a Bolognese cassetta frame with a decorative frieze usually replaced by a northern-inspired panel of gilded oak, and was probably created by Ford Madox Brown and Rossetti, and/or by G.F.Watts himself [15]. The ornament is compo, and this instance shows how thin the applied pressed decoration is, and how the aged and brittle material breaks away under stress. An inlay had been inserted, to fit it to the painting, and it was thus in every way an unsatisfactory solution – not least in the discordant colour of the gilding.

Titian or workshop, A boy with a bird, reframed in a 16th century strigillated pattern.

This solution is very similar to the frame on the Palmezzano Holy Family, only lacking its small inner astragal-&-bead moulding. This frame is even more fluid and softly-defined than the latter, and has a depth of colour and patination which harmonizes perfectly with the painting. There is no overt symbolic connection between picture and frame; however, X-rays and reflectograms of the work revealed that the boy had originally been winged, and since he is clutching one of Venus’s doves and repeats the small Cupid in the background of versions of Titian’s Venus and Adonis, [16] he has a definite pedigree linking him with a goddess born from the water. Perhaps the most obvious point to be made about this masterly reframing, however, is the extraordinary difference which can be made to an slight and rather overlooked painting by the simple act of setting it in an historically, stylistically and aesthetically appropriate frame.

************************************************************************

[1] This idea is also central to the MA thesis of Elizabeth L. Fischer, Streams of living water: the strigil motif on late antique sarcophagi re-used in mediaeval Southern France, 2011, University of North Carolina; this considers strigillation as adopted from the antique by the Christian tradition, in a metaphorical reference to baptismal waters, etc.

[2] Ibid., p.1.

[3] Ibid., p.8.

[4] Ibid., pp.18-20.

[5] Ibid., p.28-29.

[6] Ibid., p.39-40.

[7] Ibid., p.41.

[8] Ibid., p.45.

[9] Katy Gail Richardson, The context and function of four exceptions to effigial wall tomb patronage in quattrocento Florence, MA thesis, 2009, Louisiana State University.

[10] See F. Caglioti, Donatello e i Medici. Storia del David e della Giuditta, Firenze, Olschki, 2000, 2 voll. (‘Fondazione Carlo Marchi per la Diffusione della Cultura e del Civismo in Italia/ Studi’; 14), pp. 95, 96, fig. 69.

[11] It should be pointed out that documenting any of these frames is practically impossible, and possibly none of the works illustrated is in its original frame; their use for certain paintings is a choice, based on period, historical fashion and aesthetic suitability.

[12] See also the double Portrait of a man and a boy by Moroni, c.1570, Museum of Fine Art, Boston, the frame of which is similar in profile to the Cleveland painting and the Bronzino, but the leaf-&-bud near the sight edge is now a major moulding of leaf and fruit on the top edge, with an imbricated leaf above a half-flower sight edge. The latter, the centred flowers on the strigillated frieze, and the chunky fruit garland at the top edge, have a Bolognese feel to them.

[13] An almost identical pattern frames Christ of the Cross by El Greco and Jorge Manuel Theotokopoulos, John & Mable Ringling Museum of Fine Art.

[14] See Paul Joannides & Jill Dunkerton, ‘A boy with a bird in the National Gallery: two responses to a Titian question’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, vo. 28, 2007, pp.36-57.

[15] Brown and Rossetti had been using gilded oak for frames from at least 1854; Rossetti was trying to fend of its copyists by 1861. Brown described the ‘Watts’ frame in a letter of 1872 to his patron, Sir Charles Dilke, not as an invention of Watts or of anyone else, but simply as ‘a Venecian [sic] pattern (much liked now by friends of mine…)’

[16] Joannides & Dunkerton, op. cit.

Spanish or North Italian School, Head of John the Baptist, reverse of frame, Cleveland Museum of Art

Another excellent article,beautiful paintings,beautiful frames. Thank you.

LikeLike

Dear Stephen – How kind of you! Thank you very much indeed –

Lynnx

LikeLike